Multi-word expressions in the early imperial inscriptions of the I.Sicily corpus - still a pain in the neck?

Expressions such as in spite of, open-minded, and take heart are everywhere. What the three examples share is the fact that multiple words (e.g. in + spite + of) fulfil the function that a single item could (e.g. despite). We call such combinations of words multi-word expressions. If all multi-word expressions were as well behaved as our three examples – in open-minded we even have a hyphen (!) – they would be unproblematic. However, most of them are discontinuous, i.e. items can intervene between the components of the multi-word expression, e.g. I looked it up, where it is not part of the phrase look up. Many multi-word expressions are also considerably more variable than something like in spite of where any modification is unacceptable, e.g. #in great spite of, #out spite of, #in spites of. For example, we can easily turn he gave a lecture into he gave a good lecture – we know the content was sensible – and he gave the lecture well – the content might have been utter nonsense but apparently he put on a great show. Last but not least, many multi-word expressions are ambiguous. While you may not think of a cannibal ripping someone’s blood-pumping muscle out of their chest with the phrase take heart, could you be tempted to think of theft with something like to take a picture (off the mantelpiece perhaps, without asking perhaps?). The more obvious reading of to take a picture would certainly be the one in which someone uses a camera to capture a moment, but we cannot completely rule out that depending on the context it could refer to a thief sneaking in to grab a family photo (cf. Savary et al. 2018).

A pain in the neck

If you are standing on the beach and are asked to take a picture, you will be able to work out from the context that you are not being asked to make off with family photographs. But what if this context is not there? This is what language models are confronted with. When we run a language model over a text, the model will provide information such as a lemma (a dictionary form of a word), a part-of-speech tag (e.g. verb, noun, etc.), and further information. The model does this by considering each item separately. Thus, for something like to take heart the model would output take = verb and heart = noun without realising that the combination has a meaning that is totally separate from ripping a blood-pumping muscle out of someone’s chest. Multi-word expressions of all types, verbal (e.g. take heart), functional (e.g. in spite of), adjectival (e.g. open-minded), and nominal (e.g. United Kingdom), function as a unit as regards structure (syntax), meaning (semantics), and if continuous also sound (prosody). Yet, the model parses each constituent separately. Depending on the model, hyphenated multi-word expressions will fare better than non-hyphenated ones, e.g. open-minded might be parsed as an adjective rather than as open = adjective and minded = adjective (https://lindat.mff.cuni.cz/services/udpipe/run.php). Multi-word expressions really do remain a pain in the neck even twenty years after Sag et al.’s (2002) seminal article.

For the I.Sicily corpus

In the I.Sicily corpus, prosodic units can be marked with punctuation, i.e. a combination such as in spite of would receive punctuation marks before in and after of (· in spite of ·) rather than after in and spite (in spite · of) or after in and before spite (in · spite of) (https://crossreads.web.ox.ac.uk/article/dots-between-words-sicilian-inscriptions). This kind of unit-level punctuation was however never applied consistently. Nonetheless, rather than focussing on morphosyntactic words (i.e. in & spite & of), as the language model does (!), the punctuation points to prosodic words (i.e. in spite of). In the early imperial period, (prosodic) word-level punctuation appears inconsistently and more commonly in Latin than in Greek (Crellin 2022).

Let’s look at some examples from the Greek, Latin, and bilingual early imperial funerary and honorific inscriptions from Catania, Syracuse, and Termini. These can be searched via Sketch Engine (https://github.com/vbmf2/ISicily), an online corpus analysis tool with an easy to use user interface. Under ‘Concordance’, you can key in the item you are interested in in its dictionary form – we go with frons – and Sketch Engine will reveal all the contexts of interest:

Frons ‘front’ is part of a commonly appearing complex adverb (something like by contrast in English), in fronte ‘in width’ when describing the size of a memorial. It appears in inscriptions with word-level punctuation in ISic000133, ISic00136, ISic000170, ISic000214, ISic000222, and ISic000252, usually abbreviated as ‘in fr’’.

All the relevant inscriptions come from Termini. Only three times (ISic000133 (in · fr), ISic000170 (in · fronte), and ISic000252 (in · fr)), a dot appears inside the complex preposition, in two cases between the two items of the abbreviation.

A commonly appearing complex adjective is bene merenti ‘well-deserving’ when referring to the deceased for whom a memorial has been set up. It appears in inscriptions with word-level punctuation in ISic000044, ISic000092, ISic000099, ISic000115, ISic000246, ISic000372, ISic003258, and ISic003667.

Inscriptions come from all three urban hubs. Only three times (ISic000246, ISic000372, and ISic003667), a dot appears inside the complex adjective. In ISic000372 and ISic003667, both from Catania, the adjective is abbreviated as ‘b m’ with a dot in between.

The complex adverb and adjective are invariable, unambiguous, and continuous. Readers were likely familiar with these sequences, as we are with sequences such as in spite of or for your information. The latter is often abbreviated as fyi. The analogy does not extend to this extent as the exact interplay between the common Latin practice of using interpuncts in abbreviations and interpuncts in prosodic units would need further work (Prag, pc).

Abbreviations do not appear with verbal multi-word expressions. Let’s look at combinations of a verb and noun, such as do a favour, give a lecture, or take heart. These can be compositional, i.e. we can deduce the meaning of the whole from the meaning of its parts (e.g. do a favour), or non-compositional, i.e. we can only access the meaning by considering the structure as a whole (e.g. take heart – remember we are not ripping a blood pumping muscle out of anyone’s chest). In natural language processing inspired frameworks, this distinction is crucial. While most of us will judge from context whether to take a picture means nicking a family photograph or using a camera and will favour the reading of taking courage for to take heart over the rather barbaric image conjured up otherwise, a language model does not have this kind of real-life context to draw on when parsing through a text.

An example of such a natural-language-processing-inspired framework for verbal multi-word expressions is the PARSEME 1.3 universal guidelines (https://parsemefr.lis-lab.fr/parseme-st-guidelines/1.3/index.php?page=home). These distinguish verbal idioms (VID) from light-verb constructions (LVC). Verbal idioms are non-compositional (i.e. something like to take heart) whereas light-verb constructions are fully compositional (i.e. something like to give a lecture). In the I.Sicily corpus, both types appear.

ISic000406 ἐν στήθεσσιν ἔχουσειν en stēthessin ekhousein ‘to have in the chest, to have at heart, to consider in-depth’ is an example of a verbal idiom. We are not talking about a physical location – still no barbarism here. Rather, we draw on the common metaphor of heart for emotion or thought (Kraska-Szlenk 2014). From there, we can construe the meaning of the phrase. This is not a question of compositionality but transparency, i.e. we can reconstruct the meaning of a verbal idiom based on the meaning of its parts (Sheinfux et al. 2019). You could do the same with to spill the beans, i.e. beans in the sense of secrets and spill in the sense of make known, but it would not work for something like to kick the bucket which has nothing to do with buckets – although one could envisage some kind of torture method by which kicking the bucket from under someone’s feet may have the same effect.

An example of a light verb construction is ISic000957 λύσιν ἔσχε lusin eskhe ‘to have loss, to lose’.

ISic000957 Stone is lost

λύσιν ἔσχε lusin eskhe ‘to have loss, to lose’

1. ἡμέρᾳ · κυριακῇ δεσμευθεῖσα · ἀλύτοις · καμάτοις · ἐπὶ · κοίτης

2. ἧς καὶ τοὔνομα · Κυριακή · ἡμέρᾳ · κυριακῇ · παντὸς · βίου · λύσιν

3. ἔσχε τὴν ᾔτησε πρὸ · πρώτης · καλανδῶν · Μαίων · ☧

1. hēméraͅ · kuriakē̃ͅ desmeutheĩsa · alútois · kamátois · epì · koítēs

2. hē̃s kaì toúnoma · Kuriakḗ · hēméraͅ · kuriakē̃ͅ · pantòs · bíou · lúsin

3. éskhe tḕn ḗͅtēse prò · prṓtēs · kalandō̃n · Maíōn · ☧

(My translation) ‘On the day of the lord (Sunday), having been put in chains by unbreakable toils on the bed whose name is also Kuriake, on the day of the lord (Sunday), she had the loss of [sc. she lost] all life which she begged for on the first (day) before the kalendae of May (sc. the last day of April).’

In ISic000957, punctuation is applied at the level of prosodic phrases as visible with the relative pronouns that are not set off from the following noun or verb (underlined in the text). The verb ἔσχε eskhe ‘to have’ is not set off by means of punctuation from the noun λύσιν lusin ‘loss’ indicating that the two served as a prosodic unit. The line end does not necessarily count as punctuation (Crellin 2022, p. 212), although punctuation marks at the line end are comparatively rare.

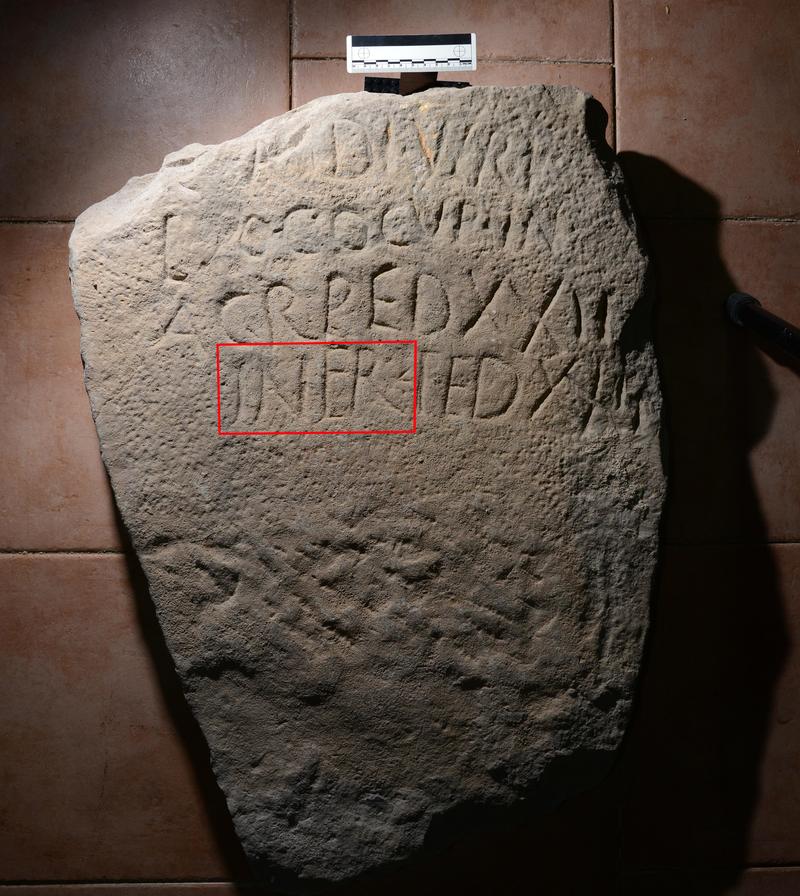

ISic001320 also shows prosodic-phrase-level punctuation. Particles, determiner phrases, and attributes that are not set off by punctuation are underlined in the text. However, verb and noun are set off by punctuation in ἀπέδωκε· χάριν apedōke kharin ‘to do / return a favour’:

ISic001320 Stone is lost

ἀπέδωκε· χάριν apedōke kharin

1. τύμβον· ὁρᾷ· ςπαροδεῖτα[πε]ρικλειτῆς

2. Ῥοδογούνης· ἣν· κτάν· ενοὐχὁσίως❦

3. λάεσιδεινὸς· ἀνήρ· κλαῦσεδὲ· καὶ· τάρ -

4. χυσε· Ἀβιάνιος· ἣν· παράκοιτιν· καὶ

5. βαιὴν· στήλῃ· τήνδ’· ἀπέδωκε· χάριν

6. ὄνομα· τὸπρίν· με· πᾶςἔκλῃζεν❦

7. ❦ Ἐπαγαθώ❦

8. νῦν· δὲῬοδογούνην· βασιλίδος

9. ❦ τὸ· ἐ· πώνυμον❦

1. túmbon · horãͅ · sparodeĩta[pe]rikleitē̃s

2. Rhodogoúnēs · hḕn · ktán · enoukhhosíōs❦

3. láesideinòs · anḗr · klaũsedè · kaì · tár -

4. khuse · Abiánios · hḕn · parákoitin · kaì

5. baiḕn · stḗlēͅ · tḗnd’ · apédōke · khárin

6. ónoma · tòprín · me · pãséklēͅzen❦

7. ❦ Epagathṓ❦

8. nũn · dèRhodogoúnēn · basilídos

9. ❦ tò · e · pṓnumon❦

‘You see the tomb, passer-by, of Rodogoune, of great fame, whom a terrible man impiously killed with stones. But Abianios mourned and buried his wife, and rendered this small favour in a stele. Everyone used to call me by the name Epagatho, but now my name is Rodogoune, the name of a queen.’ (Crellin 2022, p. 214)

The verb and the noun apparently do not form a prosodic unit. The verb ‘to return, give back’ (a verb with a prefix in Greek) is semantically heavier, i.e. closer to Mel’čuk’s (2004) verbs of realisation than to so-called light (or support) verbs as ‘to have’ in ISic000957.

We also notice that Abianios is not just rendering a favour but this small favour. Thus, we have a scenario similar to the lecture example at the start – to give a good lecture means the content is sensible, to give a lecture well may mean that the content was nonsense but the show was great. While dedicating a stele is a favour, without reading exaggerated humbleness into this text, we would hypothesise that the dedicator thinks he could have done better. The this identifies the favour with the stele in front of the reader’s eyes. A language model would not have access to this kind of contextual information.

Why bother?

Multi-word expressions in the I.Sicily corpus are important from two perspectives. From the Digital Humanities perspective, we have to decide whether to tokenize something like bene merenti well-deserving as adverb (bene) + participle (merenti from mereor) (two tokens), Option 1, or as adjective (one token), Option 2.

|

Option1 |

|

|

Option 2 |

|

|

|

Token |

Lemma |

POS |

Token |

Lemma |

POS |

|

bene |

bonus |

ADV |

benemerenti |

benemerens |

ADJ |

|

merenti |

mereor |

VERB |

|

|

|

Over time, many inflexible multi-word expressions tend towards univerbation, i.e. the fusion of two adjacent items into one (Lehmann 2020), e.g. in spite of vs. instead of and open-minded vs fainthearted. Can you still tell what the constituent parts of instead and fainthearted are? Discontinuous items must be marked as discontinuous linked tokens (see e.g. in .cupt format) to avoid parsing items of a unit separately. Language models, such as PROIEL which is commonly used on inscriptional material, do not ‘know about’ multi-word expressions. This results in misleading analyses especially at the syntactic level, i.e. do a favour is not a predicate-object structure but a complex predicate. While this is less problematic with doing favours, we may not want the model to turn take heart into a verb-object structure because that would mean a rather barbaric scene.

From the perspective of sociolinguistics, multi-word expressions are diverse as regards location, speaker group, and timeframe (what we call diatopic, diastratic, diachronic variation), e.g. do you take or have a shower (American English vs. British English), when do you make a comment and when a contribution (register), and do we take or make steps (language contact) (Langer 2005, Özbay 2020, Leech 2009, Savary and Krstev 2017)? Thus, multi-word expressions hold vital information about texts that otherwise lack secure provenance and or dating information.

References

Crellin, Robert. 2022. Word-level punctuation in Latin and Greek inscriptions from Sicily of the imperial period. In Philippa Steele & Philip Boyes (eds.), Writing around the ancient Mediterranean: practices and adaptations, 195–220. Oxford: Oxbow.

Kraska-Szlenk, Iwona. 2014. Semantic extensions of body part terms: Common patterns and their interpretation. Language Sciences 44. 15–39.

Krstev, Cvetana & Agata Savary. 2017. Games on multiword expressions for community building. INFOtheca : Journal of Information and Library Science 17(2). 7–25.

Langer, Stefan. 2004. A linguistic test battery for support verb constructions. Lingvisticæ Investigationes 27(2). 171–184.

Leech, Geoffrey. 2009. Change in contemporary English: a grammatical study. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lehmann, Christian. 2020. Univerbation. Folia Linguistica Historica 41(1). 205–252.

Mel’čuk, Igor. 2004. Verbes supports sans peine. Lingvisticæ Investigationes 27(2). 203–217.

Özbay, Ali. 2020. A Corpus Analysis of Support Verb Constructions in British English with a Specific Focus on Sociolinguistic Variables. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language) 14(2). 38–57.

Sag, Ivan, Timothy Baldwin, Francis Bond & Ann Copestake. 2002. Multiword expressions: A pain in the neck for NLP. In Alexander Gelbukh (ed.), Proceedings of the 3rd International conference on Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing, 1–15. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer.

Savary, Agata, Marie Candito, Verginica Mititelu, Eduard Bejček, Fabienne Cap, Slavomír Čéplö, Silvio Cordeiro, et al. 2018. PARSEME multilingual corpus of verbal multiword expressions. In Stella Markantonatou, Carlos Ramisch, Agata Savary & Veronika Vincze (eds.), Multiword expressions at length and in depth: Extended papers from the MWE 2017 workshop, 87–147. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Sheinfux, Livnat, Tali Greshler, Nurit Melnik & Shuly Winter. 2019. Verbal multiword expressions: Idiomaticity and flexibility. In Yannick Parmentier & Jakub Waszczuk (eds.), Representation and parsing of multiword expressions, 35–68. Berlin: Language Science Press.

ISic000957 Stone is lost

λύσιν ἔσχε lusin eskhe ‘to have loss, to lose’

1. ἡμέρᾳ · κυριακῇ δεσμευθεῖσα · ἀλύτοις · καμάτοις · ἐπὶ · κοίτης

2. ἧς καὶ τοὔνομα · Κυριακή · ἡμέρᾳ · κυριακῇ · παντὸς · βίου · λύσιν

3. ἔσχε τὴν ᾔτησε πρὸ · πρώτης · καλανδῶν · Μαίων · ☧

1. hēméraͅ · kuriakē̃ͅ desmeutheĩsa · alútois · kamátois · epì · koítēs

2. hē̃s kaì toúnoma · Kuriakḗ · hēméraͅ · kuriakē̃ͅ · pantòs · bíou · lúsin

3. éskhe tḕn ḗͅtēse prò · prṓtēs · kalandō̃n · Maíōn · ☧

(My translation) ‘On the day of the lord (Sunday), having been put in chains by unbreakable toils on the bed whose name is also Kuriake, on the day of the lord (Sunday), she had the loss of [sc. she lost] all life which she begged for on the first (day) before the kalendae of May (sc. the last day of April).’

The blog of the CROSSREADS project, based at the CSAD in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford, between 2020-2025. We will be adding regular updates on our research and news of our project publications.

CROSSREADS: text, materiality and multiculturalism at the crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 885040).