Dots between words in Sicilian inscriptions.

In English (and many other languages) we are accustomed to separating words by means of spaces. In the ancient Mediterranean world, the equivalent of the space was often the dot <·>. It may also appear as two dots placed on top of one another <:> or three dots <⋮>. We·might·separate·words·like·this·if·we·used·that·system·today.

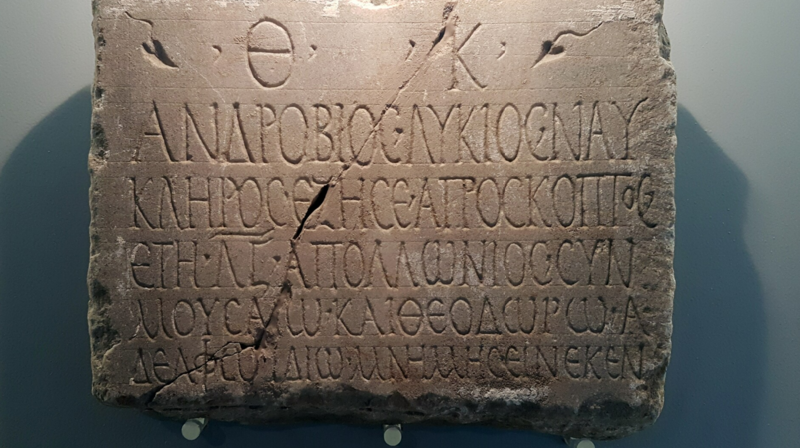

Have a look at this funerary inscription from Sicily from the first or second century ad in Sicily (ISic001231; you can find the full record here)

Fig. 1 — Funerary inscription from Sicily (first or second century AD). Photo by M. Metcalfe, 2016-12-11, courtesy Museo regionale interdisciplinare di Messina

Here is a transcription and translation:

“To the underworld deities, Androbios Lukios, shipowner, lived without offence for 36 years. Erected by his brother Apollonios, with Mousaios and Theodoros, for the memory of our brother.” (trans. per ISic001231)

For the most part, the dots correspond to where we would divide the words. In a couple of places, however, we do not find word divisions where we would expect them. The most obvious is in line 5, where we have ΚΑΙΘΕΟΔΩΡΩ instead of ΚΑΙ·ΘΕΟΔΩΡΩ “and Theodoros”. The other in line 4, where we have ΣΥΝ “with” without a following dot, before ΜΟΥΣΑΙΩ “Mousaios” on the next line. (Even though there is a line break here, we would expect to find a word divider, since we have a word divider at the end of a line in line 3; conversely there is no word divider at the end of line 2, where the word carries over to the next line.)

So what is going on? Were the writers simply a bit careless? This has often been the view in the scholarship. Either that, or that the writers were simply a bit confused about what a word is. But could there be a method in their (apparent) madness? This is the question I tried to address in my recent book The Semantics of word division in Northwest Semitic writing systems: Ugaritic, Phoenician, Hebrew, Moabite and Greek (Crellin 2022), which I wrote while working on the CREWS project in Cambridge. Since working for the Crossreads project here, I have tried to apply this research to the Sicilian inscriptions. (see Crellin forthc.).

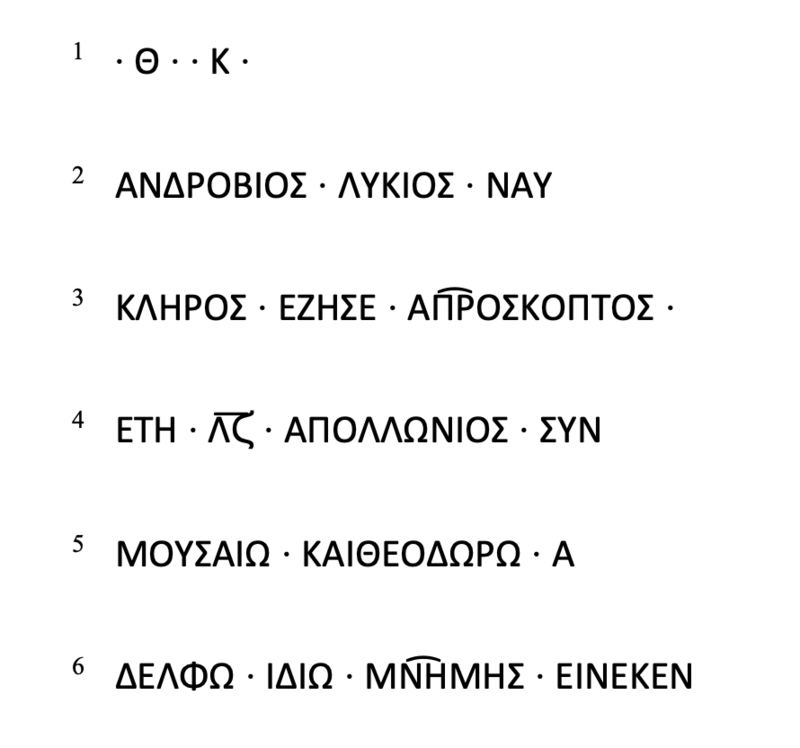

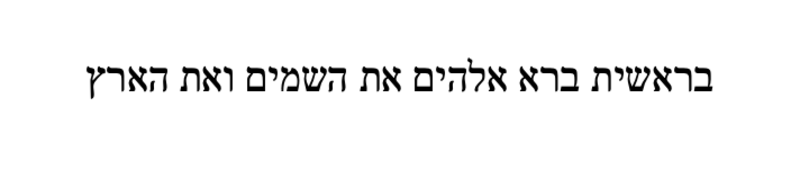

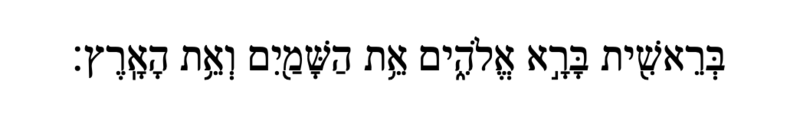

The approach to word division that we find in ISic001231 is also is also characteristic of Northwest Semitic writing systems. Have a look at the first line of the first book of the Bible, Genesis 1.1 (text taken from https://tanach.us/ with the vowels and cantillation signs removed), the so-called ‘consonantal’ text:

This is how this verse would have appeared in antiquity. The vowel points and cantillation marks that we find in Hebrew Bibles today came in in the Medieval period (https://tanach.us/):

As the following transcription of the consonantal text shows, most of the letters correspond to consonants, and the vowels are largely unwritten (the main exception being the /ī/ vowel in rˀšyt = /rēšīt/ “beginning”):

brˀšyt brˀ ˀlhym ˀt hšmym wˀt hˀrṣ

In this example there are three small words that are written together with the following words: ב b “in”, ה h “the” and ו w “and”. And in our inscription from Sicily, it is the small, monosyllabic, words ΚΑΙ “and” and ΣΥΝ “with” that don’t get their own word divider. So it seems that there are some crosslinguistic, cross-writing system parallels, for not separating these small words.

But what is the rationale for not separating off these small words? Let’s think about a sentence like:

I ate a cake for lunch.

In many ancient Greek (or Latin or Hebrew) inscriptions you get the equivalent of word division like this (there are other systems as well):

Iate·acake·forlunch.

Now have a look at where the principal accent falls on each word:

Iáte·acáke·forlúnch.

There is a correlation: there is one word divider (in our case a space) for every unit that carries a primary accent. For the inscriber of an inscription like ISic001231, a ‘word’ was an accented unit. For us, by contrast, ‘words’ are units that you might look up in a dictionary. Small words, like ‘and’, ‘a(n)’, in English and many of the world’s languages, tend not to carry their own accent, and instead rely on neighbouring words for their accentuation. This is why small words tend not to be separated off with word dividers on each side in our inscriptions.

What is the reason for ‘words’ in these inscriptions corresponding to accented units, rather than ‘dictionary’ words? Unfortunately, we can’t go back and ask. But the fact that ‘words’ are separated on this basis sits well with other things we know about how people interacted with written documents in the ancient Mediterranean world. The written word was much closer to the spoken word than it is for us: there was simply an expectation that the written word would be read aloud; even those who could read tended to read out loud to themselves, rather than silently, as we tend to do. Those who could not read would only have been able to access written documents in this way.

If interaction with the written word was primarily in the context of the spoken word, it makes complete sense to separate words on the basis of how you would say them out—rather like musical phrases—rather than on the basis of how you would look them up in a dictionary, as we do. Even something as apparently insignificant as a dot between words—or the lack thereof—can tell us something quite interesting about how different ancient societies were from our own.

I.Sicily documents

ISic001231: Prag, J. R. W., Cummings, J., Chartrand, J., Vitale, V., Metcalfe, M., Antoniou, A. and Stoyanova, S. ‘I.Sicily 001231.’ Revised 2021-01-19. http://sicily.classics.ox.ac.uk/inscription/ISic001231; doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4352237

References

Crellin, R. S. D. (2022) The Semantics of word division in Northwest Semitic writing systems: Ugaritic, Phoenician, Hebrew, Moabite and Greek. Oxford: Oxbow.

Crellin, R. S. D. (forthc.) “Word-level punctuation in Latin and Greek inscriptions from Sicily of the Imperial period." In Steele, P. M. and Boyes, P. (eds) Writing around the Mediterranean: Practices and adaptations. Oxford: Oxbow, 195–219.