The Palaeography Workshop

A workshop report: Palaeography in Ancient Mediterranean Inscriptions

Earlier this summer we held a two-day workshop bringing together scholars from Classics and adjacent fields to discuss the current state of the subject and work on establishing some strategies for the future of palaeographic analysis on epigraphic documents.

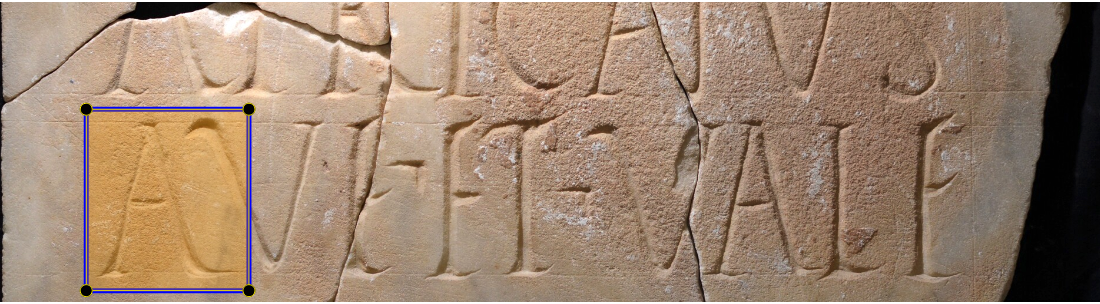

The analysis of letterforms, styles of writing and, where possible, scribal hands is an intrinsic part of the reading and interpretation of epigraphic material. Most editions of a corpus of inscriptions include some form of commentary on palaeography. However, there has never been an established, shared procedural methodology for this kind of analysis. There are no standards of describing or comparing different styles of writing or individual letterforms. Indeed, there are only a handful of dedicated publications and studies of epigraphic palaeography. Hübner’s seminal Exempla Scripturae Epigraphicae Latinae (1885) marks the first systematic study of epigraphic palaeography for Latin, both summarising the most commonly used terminology and providing lists of allographs for each letter of the alphabet; crucially, it comes with a large number of drawings. Tracy’s work on identifying and tracing the career of an Athenian mason (1975), however, provides a closer and more detailed look at a specific place and point in time. J. and A. Gordon’s Contributions to the Palaeography of Latin Inscriptions (1957) introduces some new concepts (e.g. the module as the relative configuration of the letters in terms of varying height and breadth) and suggest some clustering of matching hands as potential workshop identifications. Grasby’s studies in measurement and making of Latin inscriptions (2002) offer a more technical approach with meticulous analysis of the design, drafting, measuring, drawing and carving of inscriptions, laying out the production process.

Our workshop aimed to address the above-mentioned issues with a series of case studies and generous discussion slots. Sessions were not organised in any thematic manner, rather the goal was for each presenter to walk us through the methods and kinds of analysis they undertook in their work, as an overview of different approaches and issues around palaeography in different parts of the Mediterranean. Jonathan Prag started us off with an introduction to the scope and aims of the Crossreads project, outlining our initial efforts to create an ontology of palaeographic terms and definitions.

Charles Crowther (Oxford) then outlined his work on Hellenistic palaeography in Egypt and the particular style of dynastic inscriptions in the Kingdom of Commagene. Alison Cooley (Warwick) took us to Pompeii to discuss the variation between different texts inscribed by one individual demonstrating the importance of taking heed of the context and material support in studies of palaeographic variation. Valentina Mignosa (Udine) and Simona Marchesini (Alteritas) discussed two different approaches to modelling the seriation of inscriptions of pre-Roman Italy; Valentina explored the mechanisms underlying adoption and variation of alphabets in Archaic Sicily, while Simona showed her use of seriation models for establishing a chronology of specific pre-Roman scripts.

Yannis Kalliontzis (Athens) covered the state of affairs in Boeotia, highlighting the potential of a new photographic corpus. Hernán González Bordas (Bordeaux) introduced his work on Roman North Africa and discussed the imitation/assimilation of styles used in legal texts on public lapidary epigraphy. Coline Ruiz Darasse (Bordeaux) walked us through the new and improved Gallo-Greek corpus, which now has palaeographic annotations and comparative tables. Silvia Orlandi (La Sapienza) discussed two different methods applied on inscriptions from Rome and surroundings, one finding some correlation between linguistic and graphic innovation, and another focusing on analysis of module, ductus and furrows on late antique inscriptions. Nicolas Laubry (Paris-Est) took us further out to Ostia and Portus, showing examples of cursive writing on monuments; his paper also highlighted the importance of paying attention to the type of material, the location and intended audience of an inscription, and to genre (public, private, legal). Day one finished with a presentation and practical demonstration of letter cutting by Wayne Hart (Hart Studios) who took us through the entire process, from design to carving.

We started day 2 with Caroline Barron (Durham) on the relevance of letter forms for identifying 18th century fakes and forgeries and whether there was any awareness of the inscriptions’ authenticity, or lack thereof, in the past. Paweł Nowakowski (Warsaw) introduced his team’s work on identifying workshops in Jordan active between 3-5th century CE through drafting initial comparative lists of letterforms. Isabelle Marthot-Santaniello (Basel) gave an overview of the state of palaeography in papyrology, looking at both book hands and documentary script, tracing coherence in the evolution of letter forms and tracing similarities. Peter Stokes (ESPL) wrapped up with the past and the current development of palaeographic analytical methods in manuscript studies and beyond, and a glance into the future with efforts to compare and align several ontologies of writing.

It was an extremely valuable exercise to go through different approaches to palaeographic analysis on inscriptions ranging from archaic to late antique times and beyond, on different supports (stone, ceramic, metal, papyrus etc.) and from a variety of locations and contexts across the Mediterranean. Whereas in the Archaic Greek context the focus is on the development of the Greek alphabet and the simultaneous use of different versions of it, in the second-century imperial Roman context the questions revolve more around language contact with local communities, standardisation of official documents, trade routes and economic ties.

A number of common themes and shared issues emerged, not least the fact that palaeography is useful for addressing a variety of questions and can provide useful information about the communities involved in the creation of the inscriptions. Although there is a perception of unreliability when it comes to dating inscriptions by their letterforms, in the course of our discussions of the case studies it emerged that for most of us establishing a chronology is merely one possible facet of palaeographic analysis, and not necessarily the focus, and should always be approached with careful consideration of other dating factors. The other major uses of palaeography in ancient history that were represented at the workshop included studies looking at the intersection with material analysis, production, techniques of inscribing, the particulars of different multilingual and multicultural contexts and knowledge exchange, the relationships between official and private documents, imperial and local contexts and more.

A major point of agreement was the need for greater methodological clarity and the benefit of introducing standards to the palaeographic analysis of ancient inscriptions. We discussed initial efforts on the creation and alignment of methods, standards and typologies for describing and comparing letterforms. Aligning ongoing work to facilitate more systematic analysis would allow the study of palaeographic features at scale, whether to trace the spread and dominance of a particular alphabetic variant, to understand the knowledge exchange between communities, or to help identify clusters of workshops and artisans.

We have set up a working group which will gradually include more colleagues working on related issues and interested in driving this effort forward (anyone interested in joining this group is welcome to get in touch). In addition, an edited volume is being prepared, which will present an overview of the current state of palaeographic analysis on epigraphic material in the Mediterranean and outline ongoing work (and future plans) on methods and standards.

The blog of the CROSSREADS project, based at the CSAD in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford, between 2020-2025. We will be adding regular updates on our research and news of our project publications.

CROSSREADS: text, materiality and multiculturalism at the crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 885040).