Preparing the links: developing the I Sicily digital corpus

The digitisation of the epigraphic material in Sicily started about a decade ago with the Inscriptions of Sicily project. This epigraphic corpus, published online and in the public domain since 2017, holds all inscriptions encoded in the EpiDoc TEI XML standard and makes them available for download, enabling further research and reuse. Publishing epigraphic data alongside detailed geographical information and high-resolution images allows us to explore and analyse the epigraphic and linguistic landscape of Sicily across a greater expanse of time, and in greater detail than has ever been possible hitherto.

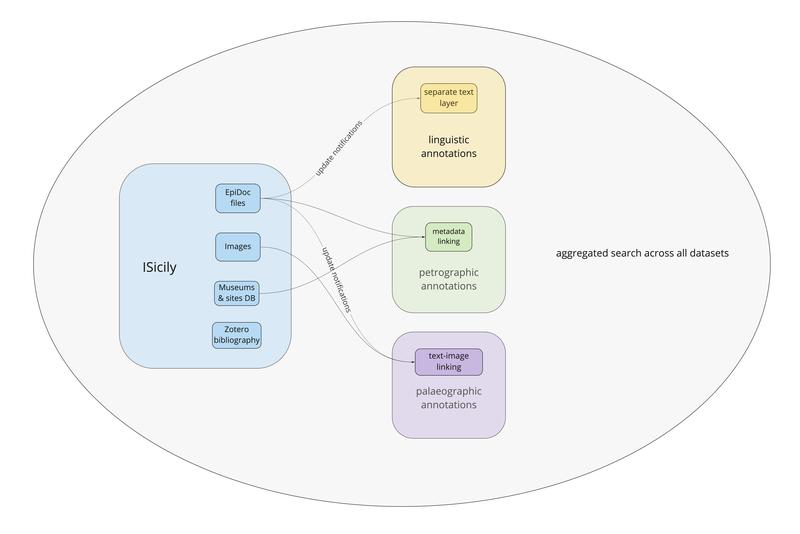

The development of the ISicily digital corpus is the overarching aim of the Crossreads project. It involves five strands of work: 1) rendering epigraphic texts in EpiDoc; 2) developing linguistic annotation on another text layer; 3) comprehensive petrographic analysis of the types of stone used for inscriptions in Sicily; 4) an image database; and 5) the systematic study of letterforms across materials, time, and language. Annotations and datasets from these work packages will be pulled together via Linked Open Data (LOD). We follow the principles of Linked Data as defined by Tim Berners Lee: by naming individual things with unique identifiers we provide further information about them in a structured machine-readable format and link them with other things in other databases in a Semantic Web. The use of LOD has become standard practice in publicly funded academic research and is a key feature of the ERC’s open access and open data research and publication policy.

We are setting up an International Interoperability Framework (IIIF) server for delivering and describing our images, a standard already in use at the Bodleian Libraries. Besides user experience features such as zoomable images, rotation etc., using the IIIF standard will, more importantly, allow us to connect our image database to those of other institutions holding open access materials on Sicily, such that we shall not need to host all available images of Sicilian inscriptions but will query their metadata directly from the data provider and serve them on our website alongside the images we host. We shall also be able to identify specific sections of an image and link them to textual content or image annotations.

Figure 1: Crossreads infrastructure.

Comparison across such diverse sets of data presents several technological challenges. In this our first year we have focused on designing the project’s infrastructure, narrowing down the protocols, standards, and technologies to use, and clean the data in preparation for this ambitious work package integration. Data management is an essential and ongoing part of the work in any research project, especially one of this scale. Without reliable data, systematically gathered and consistently encoded, analysis and discovery are bound to be slow and fraught with inaccuracies. For a brief discussion of the challenges involved in reconciling multiple datasets of cultural heritage material coming from different providers, have a look at this blog post from the LatinNow project (ERC-Starting Grant 2017, No. 715626), from February 2021.

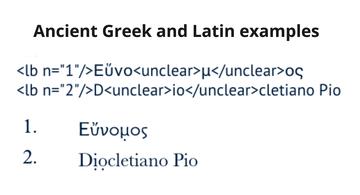

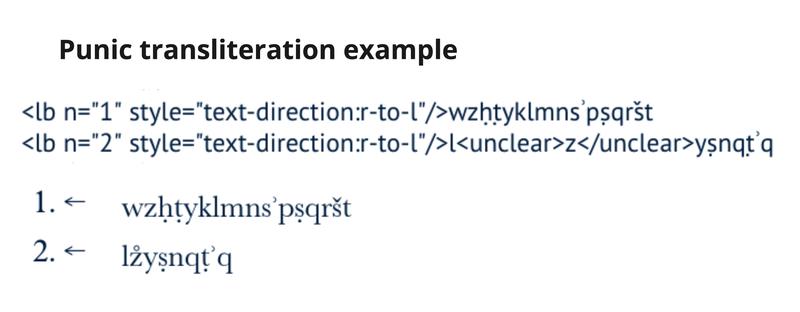

Alongside revisions of our epigraphic readings, we are acquiring additional images and more precise geographical coordinates. The latest big undertaking has been to standardise date and period expressions across the corpus: defining what Hellenistic period means in the context of Sicily, for example. We have also been pushing the boundaries of the EpiDoc standard with our array of attested languages and directions of writing. A good example is the differences in meaning of the character known as an underdot (̣).

While in Greek and Latin epigraphy it is used to indicate a partially preserved letter with an ambiguous value, in Punic it is part of the transcription into Latin characters with a phonetic value, and so partially preserved and ambiguous characters are flagged with a different symbol (̊). Thus, both conventions are encoded in the same way in EpiDoc with the '<unclear>' element but each is only allowed within the context of the language(s) used.

Figure 2a: EpiDoc encoding and visualisation of underdots in Ancient Greek and Latin texts.

Figure 2b: EpiDoc encoding and vosualisation of underdots in a transliteration of a Punic text.

A further complication is presented by the necessity to perform the linguistic annotation and analysis on a separate text layer, stripped of epigraphic editorial sigla and tokenised at the word level. This allows us to trace linguistic features across time and space, and compare the regularisations made by epigraphers to the original orthography of the inscriptions. For example, were we to revise an epigraphic reading and change a file in the epigraphic dataset, we would need to change the text in the corresponding file in the linguistic dataset. The dynamic text problem poses challenges to our workflow and infrastructure by raising several questions. At what point do we stop revising readings and decide a certain version of the text is ‘final’? If we implement and update notifications between datasets and import a change into the linguistic version of the file, do we lose the previous linguistic annotations or do we keep a history of them? Where would we keep those and how would we visualise them? What implications would they have for our linguistic analysis? Here, we are taking inspiration and guidance from our Helsinki-based colleagues behind the PapyGreek project (Digital Grammar of Greek Documentary Papyri, ERC-Starting Grant 2017, No. 758481; https://sematia.hum.helsinki.fi/) who have been annotating the EpiDoc-encoded collections from papyri.info and comparing original vs editorial versions, among other things.

One of the reasons behind our decision to tokenise texts at the word level is that it will enable us to reference specific points within the text, made possible with the Distributed Text Services (https://github.com/distributed-text-services), which is designed to facilitate referencing of texts with no canonical structure. Each token (word, name, symbol etc.) will be assigned its own identifier which, coupled with the inscription identifier – the ISic number – will provide an unambiguous reference to that token. Once we have this identifier, we can link text to image to linguistic annotation, compare versions, and see the exact rendering of the text on the original support – whether something is in ligature, partially restored, or completely supplied by an editor.

Two other work strands complete our set of five, namely the petrographic and palaeographic analysis. We have set out to achieve a comprehensive study of the petrographic features of the inscribed stones in Sicily to find out what proportion of them were either quarried locally or imported, and whether there are any geographical or chronological implications, as well as socio-economic ones. This dataset will be linked to the pre-existing metadata records we have for each inscription, these are currently rudimentary listing that something is either ‘marble’,‘limestone’, ‘breccia’ or ‘volcanic’. The petrographic dataset will sit separately from the textual ones, but it will be cross-referenced for every object.

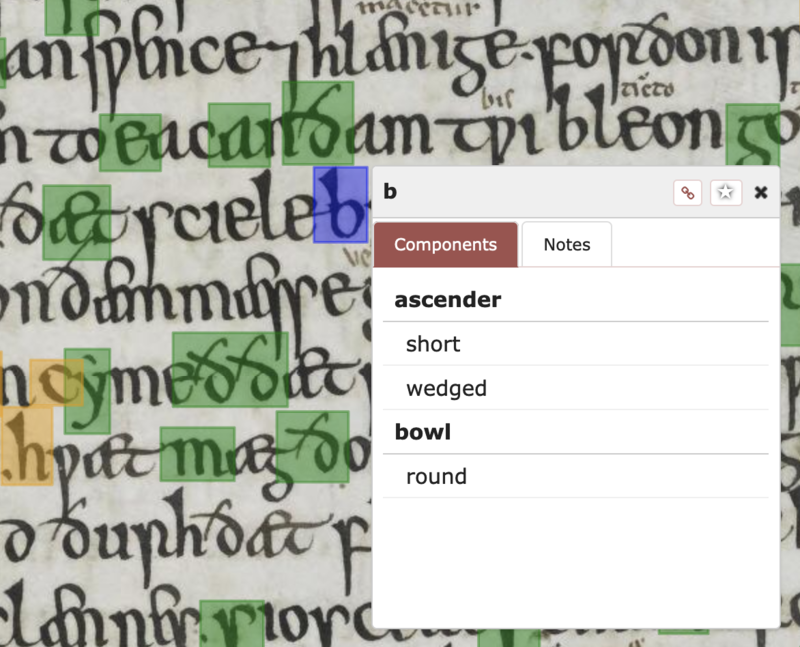

Finally, I am undertaking a systematic study of letterforms in this diverse corpus across time, supports and languages. This strand of research seeks to answer a range of questions, such as whether letterforms differ when they are rendered in different materials; whether the stone-type and surface quality influence the choice of forms; whether letter forms differ according to function, e.g., private vs public; and finally, whether letterforms can be transferred between languages. The palaeographic analysis will develop modular tools from the Archetype framework, in collaboration with King’s Digital Lab; the EpiDoc XML texts together with the IIIF image server form the basis for our palaeographic annotations and visualisation.

Figure 3: example of a palaeographic annotation on a high-resolution image from the DigiPal project (http://www.digipal.eu/), forerunner of Archetype.

The main challenge is to design an effective mechanism which will integrate information from the multiple datasets in Crossreads to enable detailed interrogation of the corpus. Pulling results from all five strands will be made possible by linking and cross-referencing key pieces of information via unique identifiers. The base text remains the epigraphic text from ISicily, the main identifier for each text is always the ISic identifier. We are in the process of modelling the data structure of the linguistic, petrographic, and palaeographic components, as well as the linking protocols for cross-referencing different types of data. The next big task will be to gain search results from all five strands of research. In addition, these results will need to be visualised effectively, linking images to text to palaeographic annotations. Our aim is to achieve all of this using linked open data principles.

The blog of the Crossreads project, based at the CSAD in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford, between 2020-2025. We will be adding regular updates on our research and news of our project publications.

Crossreads: text, materiality and multiculturalism at the crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 885040).