A curious parallel: Latin plural abbreviations and Egyptian hieroglyphs

If you’ve ever stood in front of a Latin inscription from antiquity, and tried to divine its interpretation, you will almost certainly have come across an obstacle that can severely hamper the attempt for the uninitiated: the prolific use of abbreviations. This is all the more notable since Ancient Greek inscriptions are considerably more sparing in their use of foreshortenings. Consider the following example, written on a Roman ship’s ram, in bronze, from the First Punic War (text per ISic004367):

1 C · PAPERIO · TI · F

2 M · POPULICIO · L · F · Q · P

As may be seen from the following expanded text, all the words involve some kind of abbreviation (reading and translation per ISic004367):

1 C(aios) · PAPERIO(s) · TI(beri) · F(ilios)

2 M(arcos) · POPULICIO(s) · L(ucii) · F(ilios) · Q(uaestores) · P(robaverunt)

“Gaius Papirius, son of Tiberius, (and) Marcus Publicius, son of Lucius, quaestors, approved (this ram)”

Of course, we are all too familiar with Latin abbreviations from our own (written and spoken) language, perhaps so familiar that we don’t notice. We have a number of Latin abbreviations in regular use, including <e.g.> exempli gratia “for the sake of example”, <i.e.> id est “that is”, <NB> nota bene “note well”, <etc.> et cetera “and the rest”. Yet another form of abbreviation is the ligature, as in ampersand <&> et “and”.

Latin abbreviation may take various forms (typology and examples per Cooley 2012, 359):

- Suspension (= omission of the end of the word), e.g. <IMP> imp(erator) “general”;

- Contraction (= omission of letters from the middle of the word), e.g. <PBR> p(res)b(ite)r “elder”;

- Contraction with suspension, e.g. <QQ> q(uin)q(uennalis) “quinquennial”;

- Doubling / tripling for pluralization, e.g. <AVGG NN> Aug(usti) n(ostri), (lit. “our Augusti”, referring to two emperors); <AVGGG NNN>, (lit. “our Augusti”, referring to three emperors) (see also Stevenson 1889, 95).

It is the fourth type, doubling or tripling of the abbreviation’s final character, that I wish to focus on here. This is perhaps the least familiar abbrevation strategy from our own context, although you do occasionally find abbreviations such as <exx.> for exempla “examples”.

To see how this is used in context, have a look at Figure 1, which shows a bronze nummus of Constantius I Chlorus, from 300 AD.

SACRA MONET AVGG ET CAESS NOSTR

Sacra Monet(a) Aug(ustorum) et Caes(arum) nostr(orum)

“Holy Moneta of our Augusti and Caesars”

The coin comes from the Tetrarchy, under which the Empire was ruled by two senior emperors (Augusti) and two junior emperors (Caesares) (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetrarchy, accessed 15th May 2022). In the coin inscription <AUGG> and <CAESS> denote the plurals of Augustus and Caesar respectively: because there are two in each case, the final letter of the abbreviations are doubled (rather than tripled).

This means of denoting a word’s plural form is striking, since it bears no reference to the form one might actually say: the plural forms nostri / nostrorum was always pronounced nostri / nostrorum, never nnn! Rather, the plural is denoted through reference to the underlying idea, that of plurality, and it does this, by multiplying the (final or only) character. What makes this abbreviation strategy doubly remarkable is that it has an almost exact parallel in (Old) Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, that is, from a context thousands of years older, and almost as many miles distant.

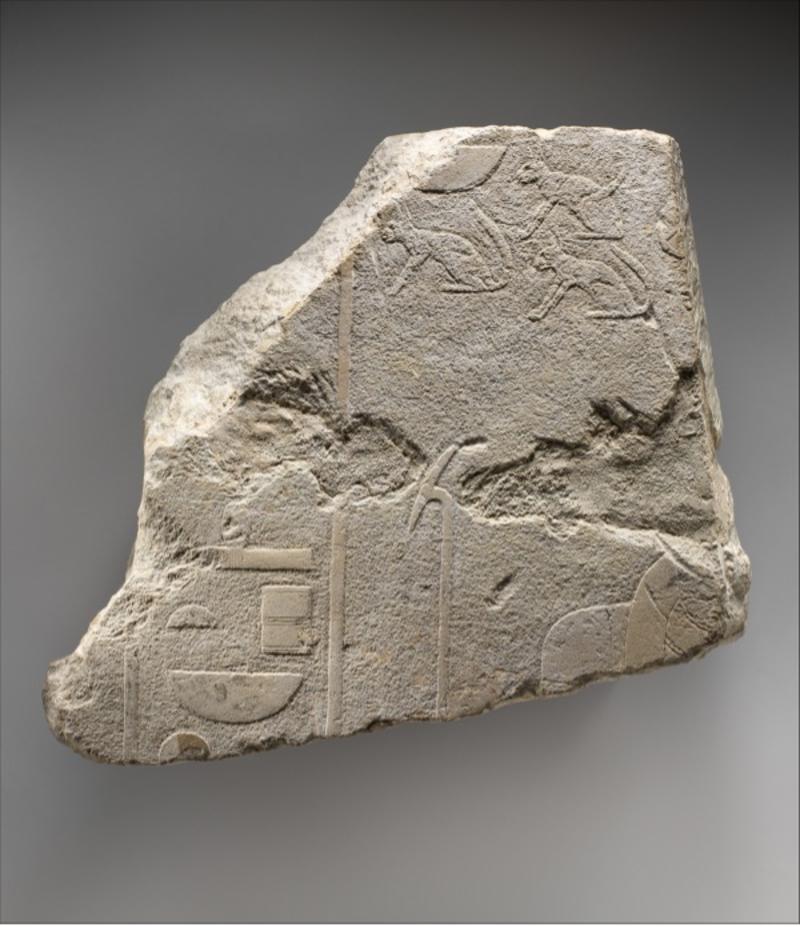

Egyptian hieroglyphs can represent one, two, or three-consonants of the spoken language. Take, for example, the word for ‘god’, whose consonants are nṯr, and which is traditionally pronounced necher (Egyptian didn’t record vowels until much later in its written history). This word is often written using a single hieroglyph, viz. <𓊹>. The plural of masculine nouns, like nṯr, is usually -w, nṯrw, which would imply a hieroglyphic form <𓊹𓅱>. However, the plural form isn’t written by adding the quail chick <𓅱>. (Indeed, the addition of this character is rarely the exclusive means of denoting plural Allen 2014: 45.) In the case of nṯr, the plural is written by repeating the ‘root’ sign three times, i.e. <𓊹𓊹𓊹>, (Allen 2014: 46; Nederhof & Rahman 2017: 140). In the case of <𓃠> miw (!) “cat”, the plural is written <𓃠𓃠𓃠>, as in the inscription shown in Figure 2, <𓎟𓃠𓃠𓃠𓊖>.

Fig. 2 — Later Old Kingdom inscription (ca. 2353–2150 BCE) denoting a town with the name ‘Lord of cats’.

Public domain image from the New York Met (or details and the original image, see https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/551093).

These are almost exact parallels of <NNN> for Latin nostri that we saw above: first the word nostri is represented by a single character, <N>. The plural is then formed, not by adding a graphical representation of the plural of the spoken language, e.g. -i, to form *<Ni> for nostri, for example, but by multiplying the single character three times, to make <NNN>.

The strategy is also used for pluralising longer words, too. Take, for example, the word <𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀> ḥqꜣ “ruler”. This form is composed to two constituents. Each character of the sequence <𓎛𓈎𓄿> corresponds to a single consonant of the spoken language, viz.. ḥqꜣ. We then have an additionally character: <𓀀>. This character is known as a ‘determinative’ (for further details, see Allen 2014, 35). It isn’t pronounced, but helps the reader to classify the foregoing characters according to semantic category. In this case, the character <𓀀> is simply the determinative used for typically male occupations or roles (cf. Allen 2014, 467).

If you want to pluralise <𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀> ḥqꜣ, you usually don’t multiply the entire sequence, viz. *<𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀>, although this strategy is occasionally found (Nederhof & Rahman 2017: 141; Allen 2014: 46). Instead, you multiply the final character, the determinative, to produce <𓎛𓈎𓄿𓀀𓀀𓀀> ḥqꜣw (Nederhof & Rahman 2017: 140–141; Allen 2014: 45; Sproat 2000: 54–55). This in turn provides an almost exact parallel for our Latin example <AUGGG> Augusti “Augustuses”. Latin, of course, has no determinatives; instead for <AVGG> and <AVGGG>, the final character of the abbreviated form <AVG> is repeated instead.

This is not to suggest that there is any direct link between these two pluralisation strategies, not least since the multiplicative strategy of Egyptian is a feature of the earliest phase of the written language. Rather, it shows that different societies, in very different times and places, have arrived at remarkably similar solutions to the same problem: how to write the plural form of a word. The solution they found involves no direct reference to the spoken form of the language, as is the case—at least in origin—with many writing systems in the world, but rather to the idea they were seeking to express, that of plurality itself.

Acknowledgements

The present article was written as part of ongoing research on the CROSSREADS project. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 885040).

I.Sicily documents

ISic004367: Prag, J. R. W., Cummings, J., Chartrand, J., Vitale, V., Metcalfe, M. and Stoyanova, S. ‘I.Sicily 004367.’ Revised 2021-01-19. http://sicily.classics.ox.ac.uk/inscription/ISic004367; doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4381814

References

Allen, J. P. (2014) Middle Egyptian: An introduction to the language and culture of hieroglyphs, 3rd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooley, A. (2012) The Cambridge handbook to Latin epigraphy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nederhof, M. and Rahman, F. (2017) ‘A probabilistic model of Ancient Egyptian writing’, Journal of Language Modelling 5(1), 131-163.

Sproat, R. (2000) A computational theory of writing systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stevenson, S. W. (1889) A dictionary of Roman coins: Roman and Imperial. London: George Bell.

The blog of the CROSSREADS project, based at the CSAD in the Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford, between 2020-2025. We will be adding regular updates on our research and news of our project publications.

CROSSREADS: text, materiality and multiculturalism at the crossroads of the ancient Mediterranean has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 885040).